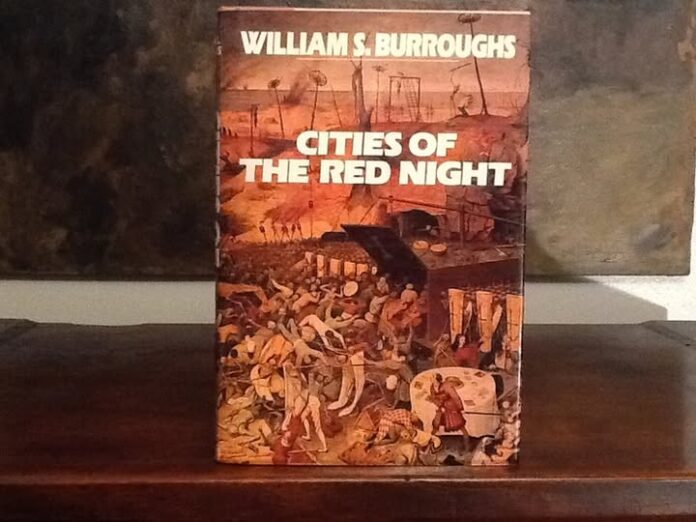

I picked up Cities of the Red Night by William S. Burroughs on a restless evening, drawn by its reputation as a boundary-shattering work from a literary icon. Published in 1981 as the first part of Burroughs’ Red Night Trilogy, this novel has since unraveled my sense of reality over the past few months, its fragmented, nightmarish narrative seeping into my thoughts with an intensity I couldn’t have predicted.

The book immerses readers in a disorienting, time-bending descent into a world where rebellion, disease, and desire collide in a hallucinatory tapestry. It weaves three interwoven threads that defy conventional storytelling, a hallmark of Burroughs’ nonlinear style. In the 18th century, a band of radical pirates, led by the young gunsmith Noah Blake, seeks to establish a utopian society under the libertarian Articles of Captain James Mission. Inspired by the historical rumor of Mission’s commune, Libertatia, Burroughs reimagines this haven as a defiant stand against the colonial powers of Europe, though their dream of freedom is shadowed by the era’s brutal realities—slavery, exploitation, and the constant threat of betrayal. In a parallel late-20th-century narrative, Clem Snide, a cynical detective—or “private asshole,” as Burroughs dubs him—investigates the disappearance of a boy named Jerry Green. Snide’s search uncovers a sinister network of ritualistic hangings, sexual cults, and a deadly radiation virus called B-23, which spreads through sexual contact, causing grotesque symptoms like blotchy skin, erotic convulsions, and eventual death, casting an apocalyptic shadow over the modern world that eerily foreshadows the AIDS crisis.

At the novel’s core are the six mythical Cities of the Red Night—Tamaghis, Ba’dan, Yass-Waddah, Waghdas, Naufana, and Ghadis—set in the Gobi Desert 100,000 years ago, yet hauntingly present in the other timelines through dreamlike visions and a pervasive sense of doom. Inspired by magical incantations Burroughs studied with artist Brion Gysin and the medieval Arabic text Picatrix, these cities operate under the creed “Nothing is true, everything is permitted,” a phrase attributed to Hassan-i Sabbah that encapsulates the book’s anarchic ethos. In Waghdas, a cholera-like epidemic—later revealed as a sexually transmitted virus—ravages the population, linking the ancient and modern narratives through themes of contagion, both physical and cultural. Burroughs’ recurring motifs of hanging and auto-erotic asphyxiation serve as a symbolic thread, tying the timelines together as characters across centuries grapple with the intersection of sex, death, and liberation.

Burroughs, a Beat Generation icon whose life was marked by addiction, exile, and the tragic 1951 manslaughter of his wife Joan Vollmer in Mexico City, infuses the novel with his personal obsessions. Having settled in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1981 while writing the book, he constructs an alternate history that rejects the horrors of colonialism and centralized authority, envisioning a world where pirate communes flourish as bastions of liberty. Yet the novel’s surreal, often grotesque elements—graphic depictions of drug use, ritualistic sex, and a mythology involving the transmigration of souls—challenge readers to navigate a narrative that feels like a fever dream. The three strands eventually converge in a chaotic finale, blending timelines in a hallucinatory clash that some interpret as a dream, others as a theatrical allegory, leaving readers with a lingering sense of unease and countless unanswered questions.

Reading Cities of the Red Night in 2025, I’m struck by its chilling prescience. The B-23 virus mirrors modern pandemics like COVID-19, while the social alienation of the characters resonates with our hyper-digital age, where genuine connection often gives way to virtual facades. The pirate utopias, meanwhile, speak to a yearning for freedom amid rising authoritarianism and corporate control, a tension that feels all too relevant today. Burroughs’ prose, often described as cold and fragmented, creates a strange beauty born of terror—a “modern Inferno,” as Newsday aptly called it. Norman Mailer once hailed Burroughs as “the only American writer who may be conceivably possessed by genius,” and here, that genius manifests in his ability to craft a private mythology unbound by time, reminiscent of William Blake’s apocalyptic visions. Yet the novel’s explicit content and nonlinear structure aren’t for the faint of heart; as some Goodreads reviews note, its stream-of-consciousness leaps and dreamlike sequences demand patience, often leaving readers disoriented as they piece together what’s real within the story’s layered narratives.

For me, Cities of the Red Night was a descent into a world where reality fractures, leaving behind a haunting unease. Its exploration of freedom, control, and the viral nature of human desire—both literal and metaphorical—feels as urgent now as it did in 1981. This isn’t just a novel; it’s a mind-altering journey, a testament to Burroughs’ unrelenting vision, and a stark reminder of the price of living on society’s fringes. Somewhere, I imagine, a restless soul is discovering this book, ready to be swept into its strange, apocalyptic magic, just as I was.